Transcript:

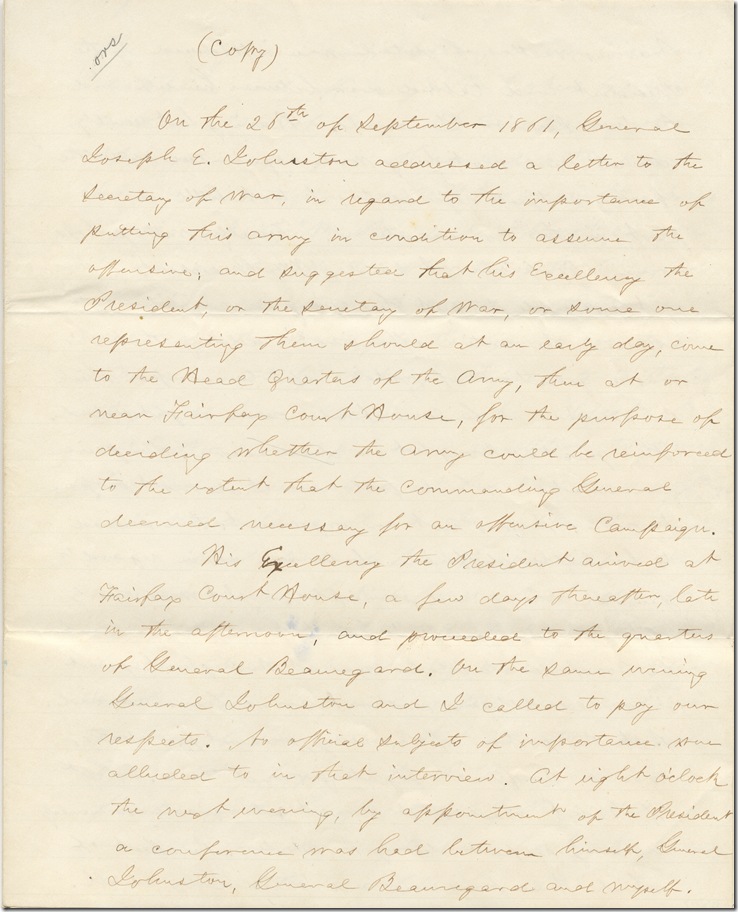

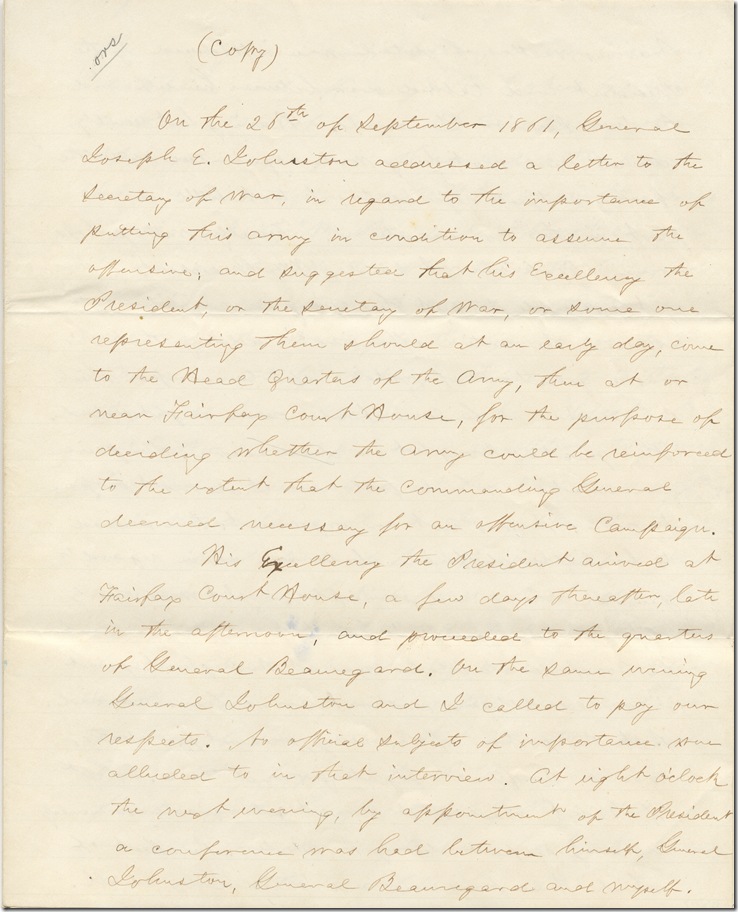

On the 26th of September 1861, General Joseph E. Johnston addressed a letter to the Secretary of War, in regard to the importance of putting this army in condition to assume the offensive; and suggested that his Excellency the President, or the Secretary of War, or some one representing them should at an early day, come to the Head Quarters of the Army, then at or near Fairfax Court House, for the purpose of deciding whether the Army could be reinforced to the extent that the Commanding General deemed necessary for an offensive Campaign.

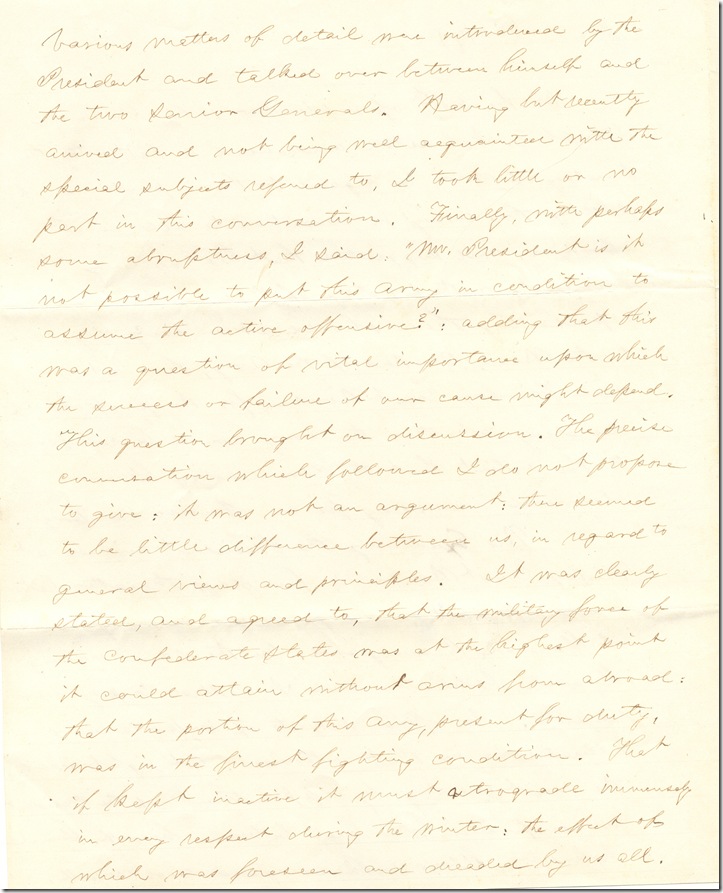

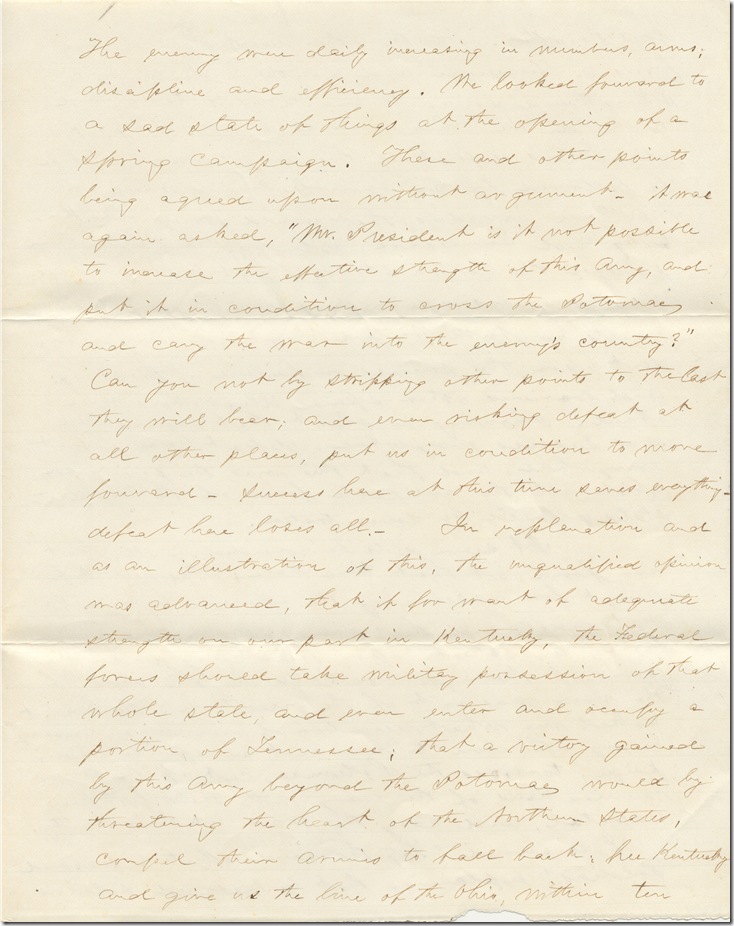

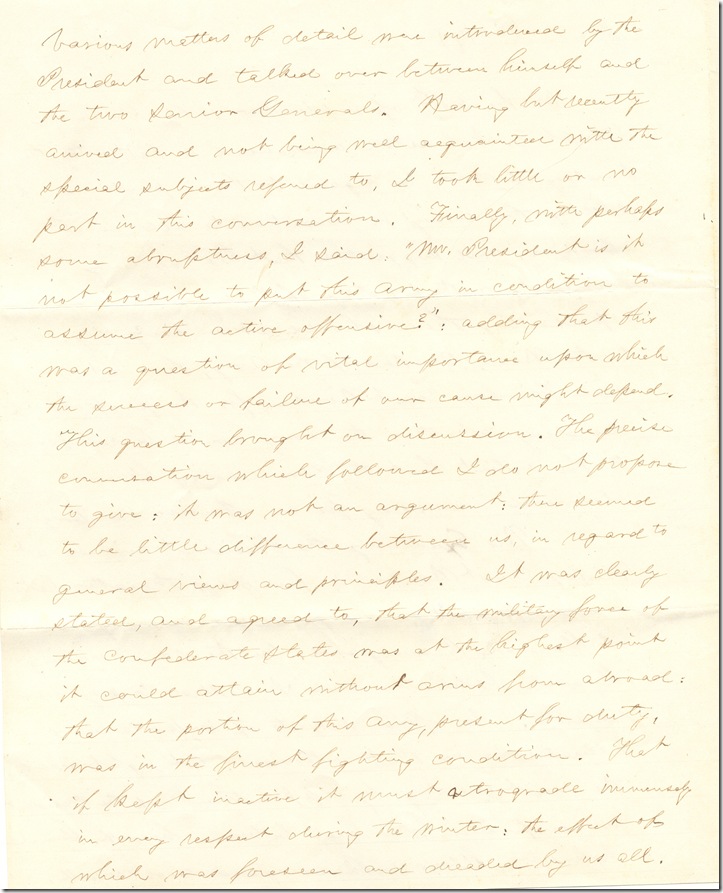

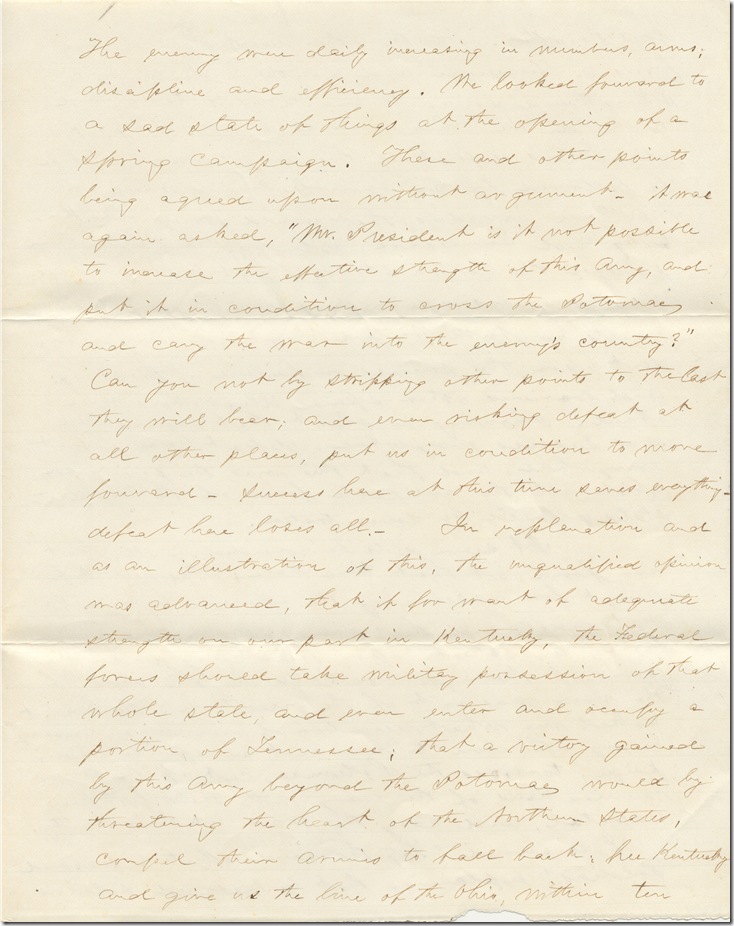

His Excellency the President arrived at Fairfax Court House, a few days thereafter, late in the afternoon, and proceeded to the quarters of General Beauregard. On the same evening General Johnston and I called to pay our respects. No official subjects of importance were alluded to in that interview. At eight o’clock the next evening, by appointment of the President a conference was had between himself, General Johnston, General Beauregard, and myself. Various matters of detail were introduced by the President and talked over between himself and the two senior Generals. Having but recently arrived and not being well acquainted with the special subjects referred to, I took little or no part in this conversation. Finally, with perhaps some abruptness, I said: “Mr. President is it not possible to put this Army in condition to assume the active offensive?”: adding that this was a question of vital importance upon which the success or failure of our cause might depend. This question brought on discussion. The precise conversation which followed I do not propose to give: it was not an argument: there seemed to be little difference between us, in regard to general views and principles. It was clearly stated, and agreed to, that the military force of the Confederate States was at the highest point it could attain without arms from abroad: that the portion of this Army, present for duty, was in the finest fighting condition. That it kept inactive it must retrograde immensely in every respect during the winter: the effect of which was foreseen and dreaded by us all. The enemy were daily increasing in numbers, arms, discipline and efficiency. We looked forward to a sad state of things at the opening of a spring campaign. These and other points being agreed upon without argument- it was again asked, “Mr. President is it not possible to increase the effective strength of this Army, and put it in condition to cross the Potomac and carry the men into the enemy’s country?” Can you not by stripping other points to the least they will bear; and even risking defeat at all other places, put us in condition to move forward- success here at this time saves everything- defeat here loses all.- In explanation and as an illustration of this, the unqualified opinion was addressed, that if for want of adequate strength on our part in Kentucky, the Federal forces should take military possession of that whole state, and even enter and occupy a portion of Tennessee; that a victory gained by this Army beyond the Potomac would by threatening the heart of the Northern States, compel their Armies to fall back: free Kentucky, and give us the line of the Ohio, within ten days thereafter. On the other hand should our forces in Tennessee and Southern Kentucky be strengthened so as to enable us to take and to hold the Ohio river as a boundary: a disastrous defeat of this Army, would at once be followed by an overwhelming share of Northern invaders, that would sweep over Kentucky and Tennessee, extending to the Northern part of the cotton states: if not to New Orleans. Similar views were expressed, in regard to ultimate results in North Western Virginia being dependent upon the success or failure of this Army: and various other special illustrations were offered. Showing in short that success here was success everywhere- defeat here, defeat everywhere: and that this was the point upon which all the available force of the Confederate States should be concentrated.

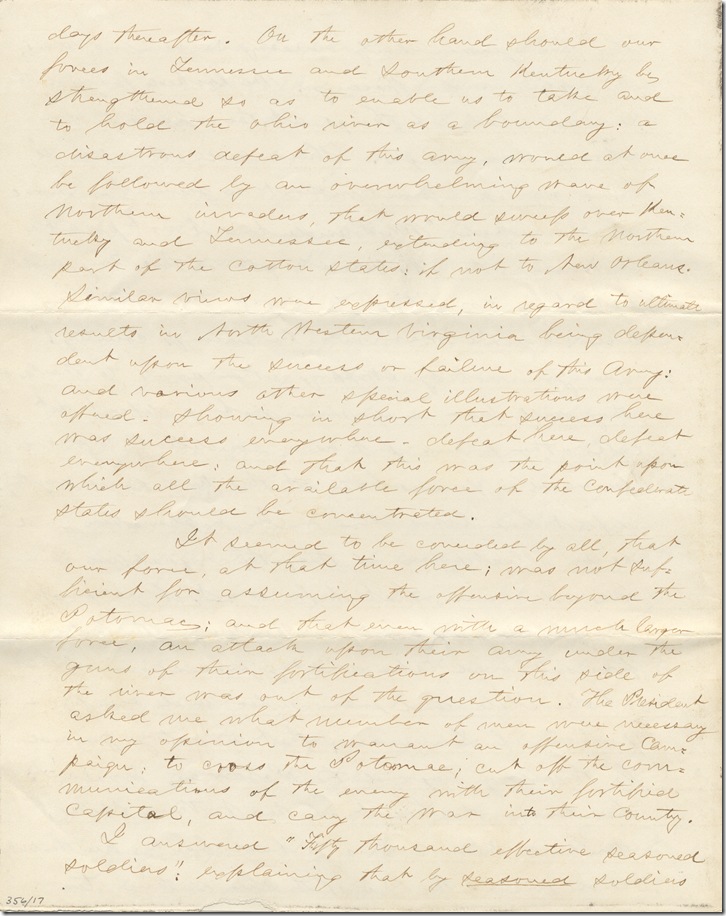

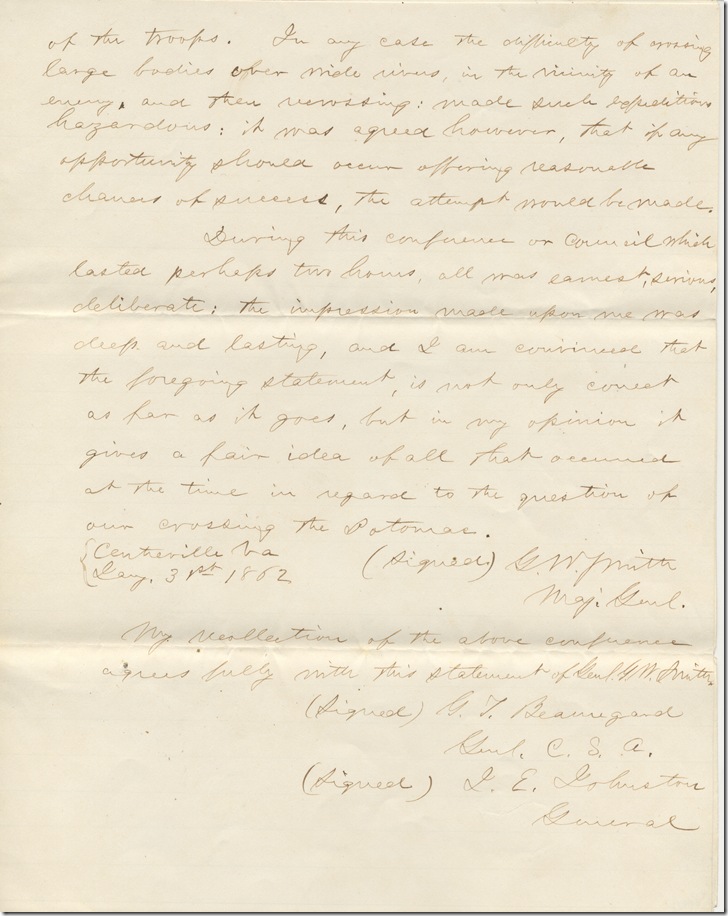

It seemed to be considered by all, that our force, at that time here; was not sufficient for assuming the offensive beyond the Potomac; and that even with a much larger force, an attack upon their Army under the guard of their fortifications on this side of the river was out of the question. The President asked me what number of men were necessary in my opinion to mount an offensive campaign: to cross the Potomac; cut off the communications of the enemy with their fortified capitol; and carry the men into their country.

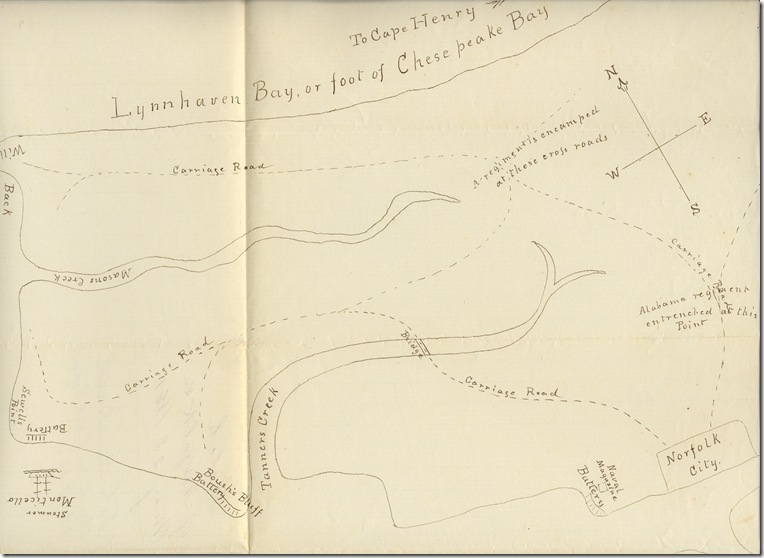

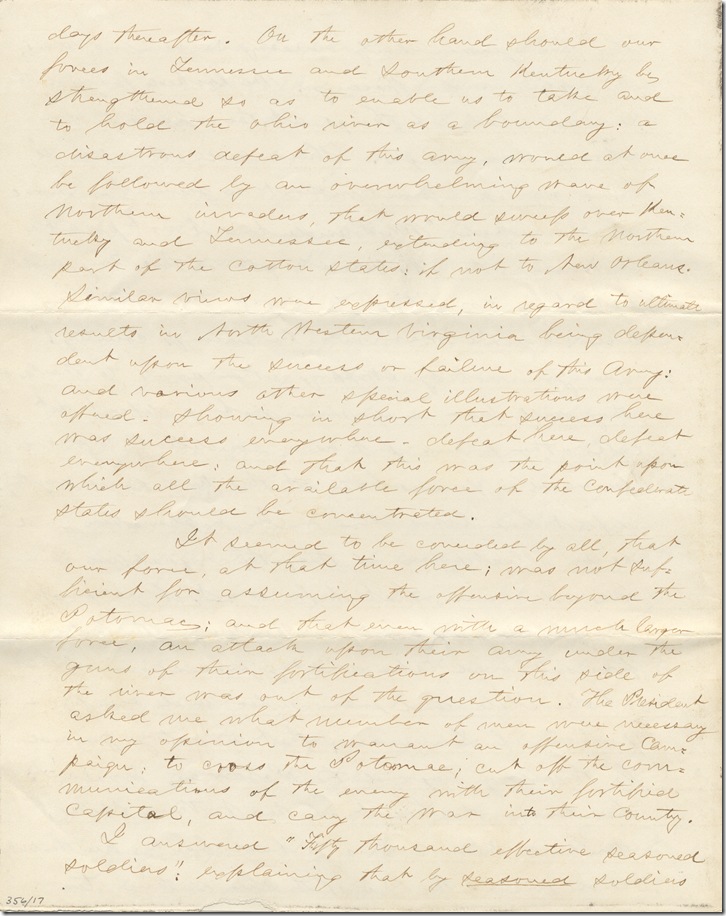

I answered “Fifty thousand effective seasoned soldiers”: explaining that by seasoned soldiers I meant such men as we had here, present for duty. And added that they would have to be drawn from the Peninsula, about Yorktown- Norfolk- from Western Virginia- Pensacola, or wherever might be most expedient.

General Johnston and General Beauregard both said, that a force of sixty thousand such men would be necessary: and that this force would require large additional transportation, and munitions of war: the supplies here being entirely inadequate for an active campaign in the enemy’s country even with our present force. In this connection there was some discussion of the difficulties to be overcome, and the probabilities of success: but no one questioned the disastrous results of remaining inactive throughout the winter.

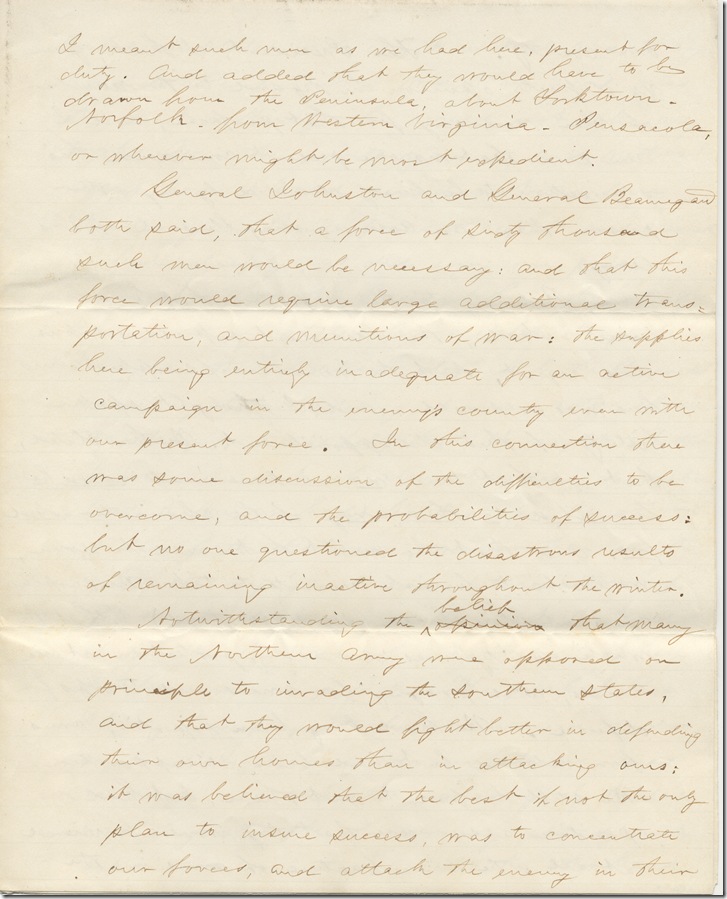

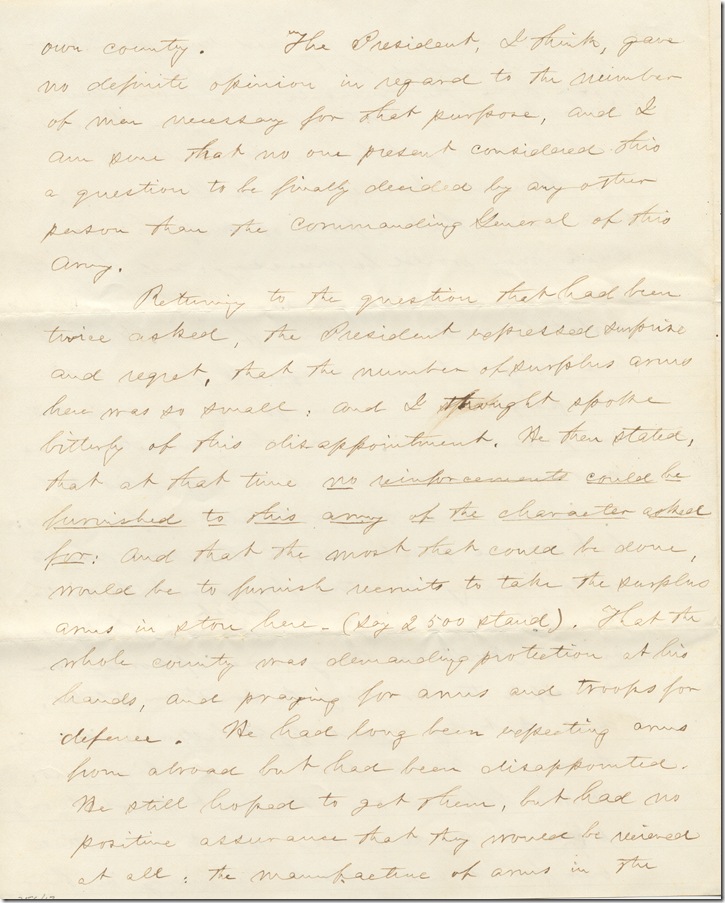

Notwithstanding the belief that many in the Northern Army were opposed on principle to invading the Southern States, and that they would fight better in defending their own homes than in attacking arms: it was believed that the best is not the only plan to insure success, was to concentrate our forces, and attack the enemy in their own country. The President, I think, gave no definite opinion in regard to the number of men necessary for that purpose, and I am sure that no one present considered this a question to be finally decided by any other person than the commanding General of this Army.

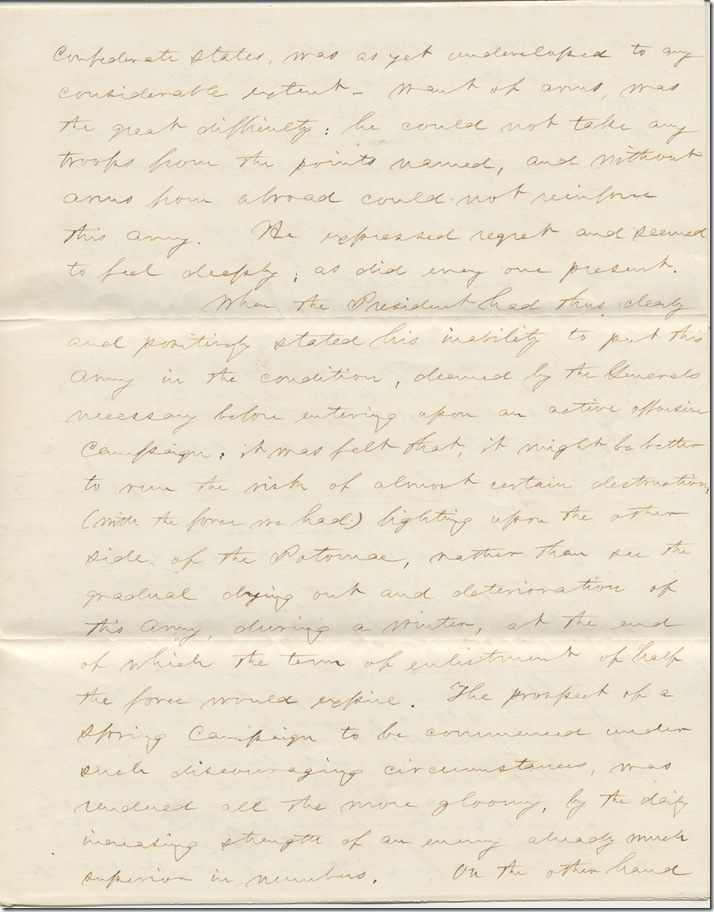

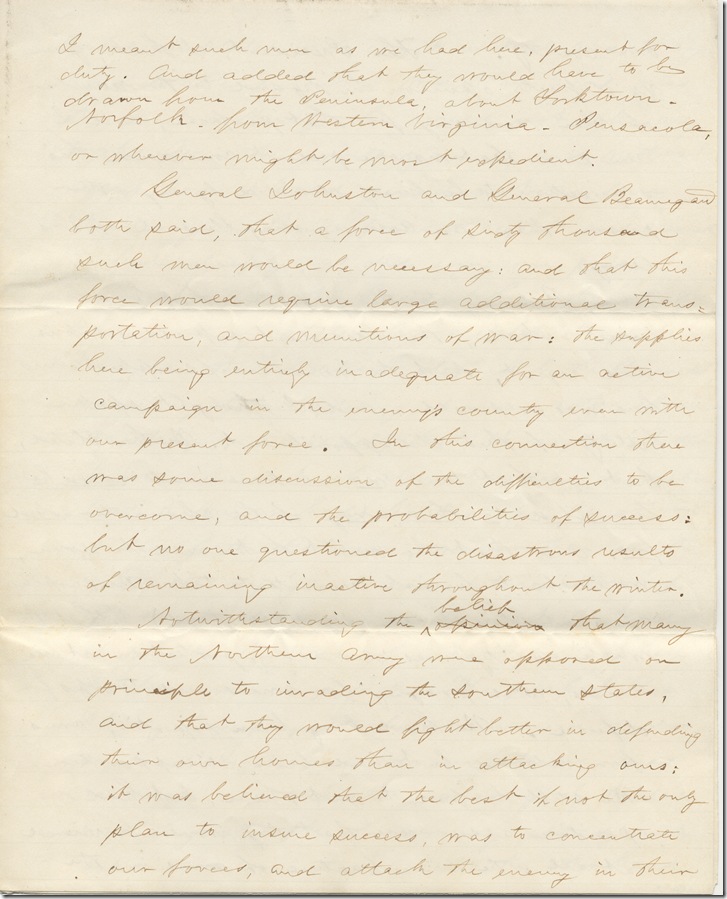

Returning to the question that had been twice asked, the President expressed surprise and regret, that the number of surplus arms here was so small: and I thought spoke bitterly of this disappointment. He then stated, that at that time no reinforcements could be furnished to this army of the character asked for: And that the most that could be done, would be to furnish recruits to take the surplus arms in store here (say 2500 stand). That the whole country was demanding protection at his hands, and praying for arms and troops for defence. He had long been expecting arms from abroad but had been disappointed. He still hoped to get them, but had no positive assurances that they would be received at all: the manufacture of arms in the Confederate States, was as yet undeveloped to any considerable extent- want of arms, was the great difficulty: he could not take any troops from the points named, and without arms from abroad could not reinforce this Army. He expressed regret and seemed to feel deeply: as did every one present.

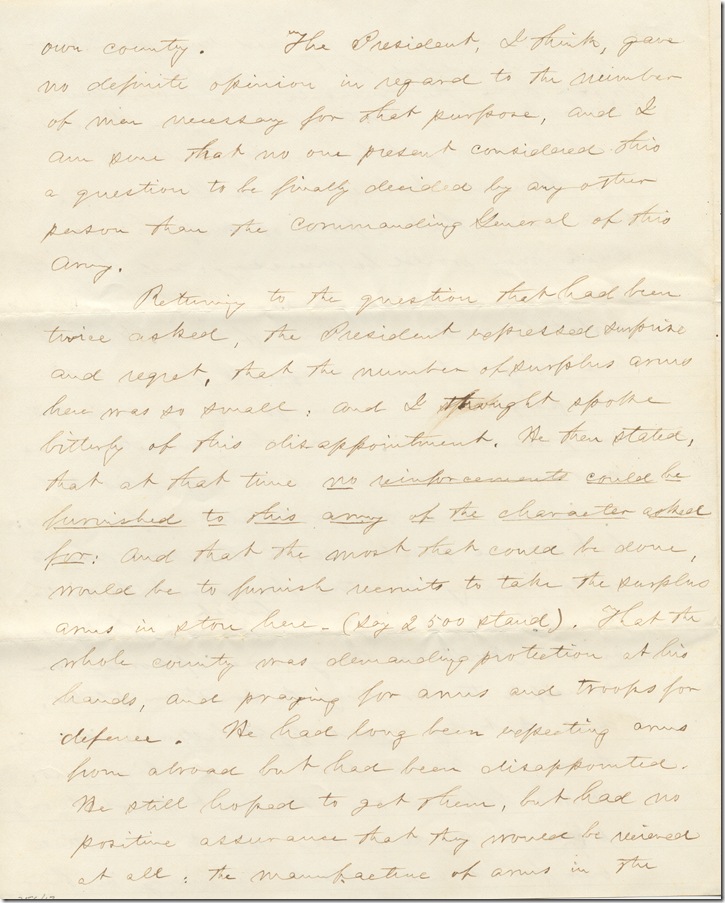

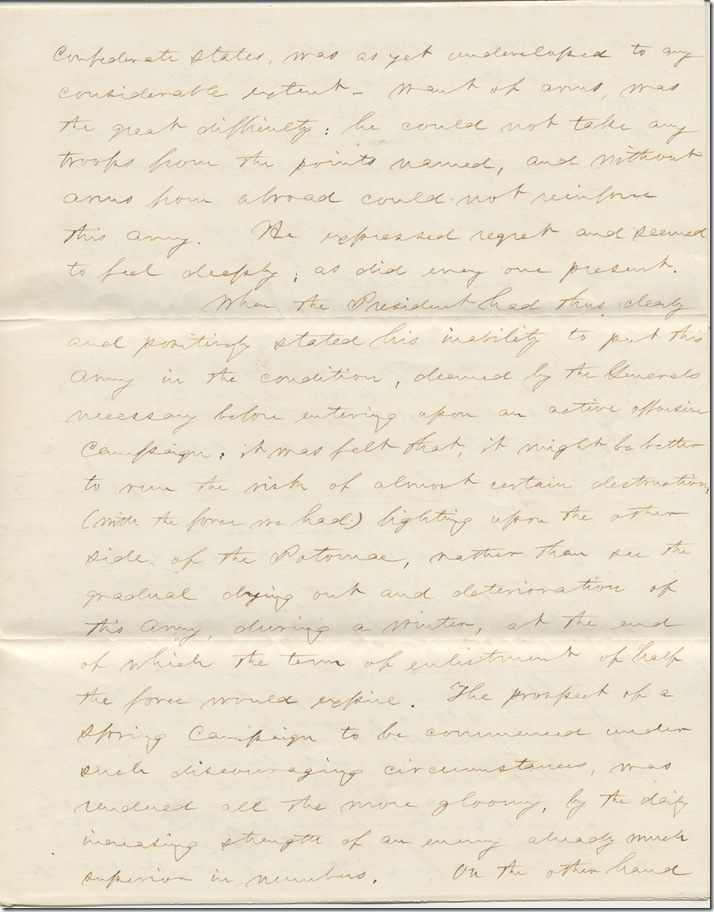

When the President had thus clearly and positively stated his inability to put the Army in the condition, deemed by the Generals necessary before entering upon an active offensive campaign: it was felt that, it might be better to run the risk of almost certain destruction, (with the force we had) fighting upon the other side of the Potomac, rather than see the gradual dying out and deterioration of this Army, during a winter, at the end of which the term of enlistment of half the force would expire. The prospect of a spring campaign to be commenced under such discouraging circumstances, was rendered all the more gloomy, by the daily increasing strength of an enemy already much superior in numbers. On the other hand was the hope and expectation that before the end of winter, arms would be introduced into the country: and all were confident, that we could then not only protect our own country, but successfully invade that of the enemy.

General Johnston said, that he did not feel at liberty, to express an opinion as to the practicality of reducing the strength of our forces, at points not within the limits of his command: and with but few further remarks from any one, the answer of the President was accepted as final, and it was fact, that, there was no other course left, but to take a defensive position, and await the enemy. If they did not advance we had but to await the winter and its results.

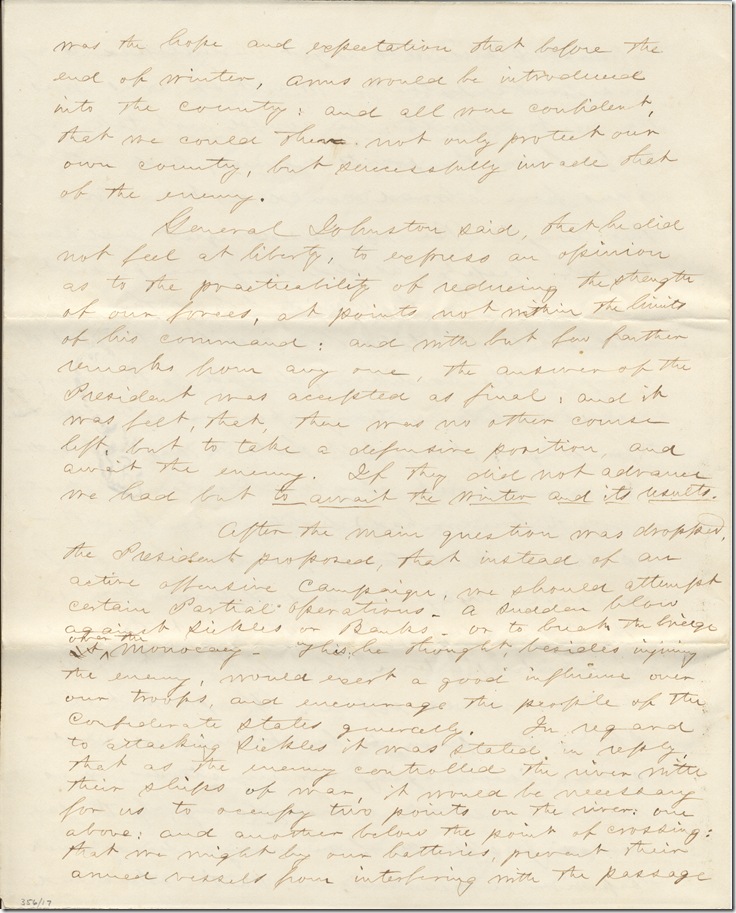

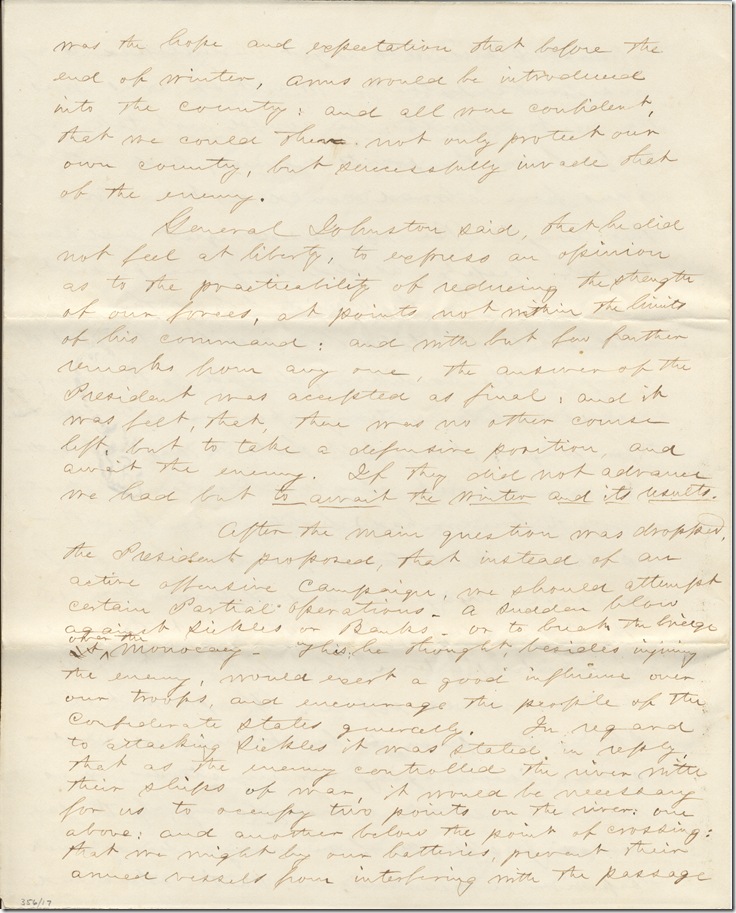

After the main question was dropped, the President proposed, that instead of an active offensive campaign, we should attempt certain Partial operations- a sudden blow against Sickles or Banks- or to break the siege over the Monocacy- This he thought, besides injuring the enemy, would exert a good influence over our troops, and encourage the people of the Confederate States generally. In regard to attacking Sickles it was stated in reply, that as the enemy controlled the river with their ships of war, it would be necessary for us to occupy two points on the river: one above: and another below the point of crossing: that we might by our batteries, prevent their unused vessels from interfering with the passage of the troops. In any case the difficulty of crossing large bodies over wide rivers, in the vicinity of an enemy and then recrossing: made such expedition hazardous: it was agreed however, that if any opportunity should occur offering reasonable chances of success, the attempt would be made.

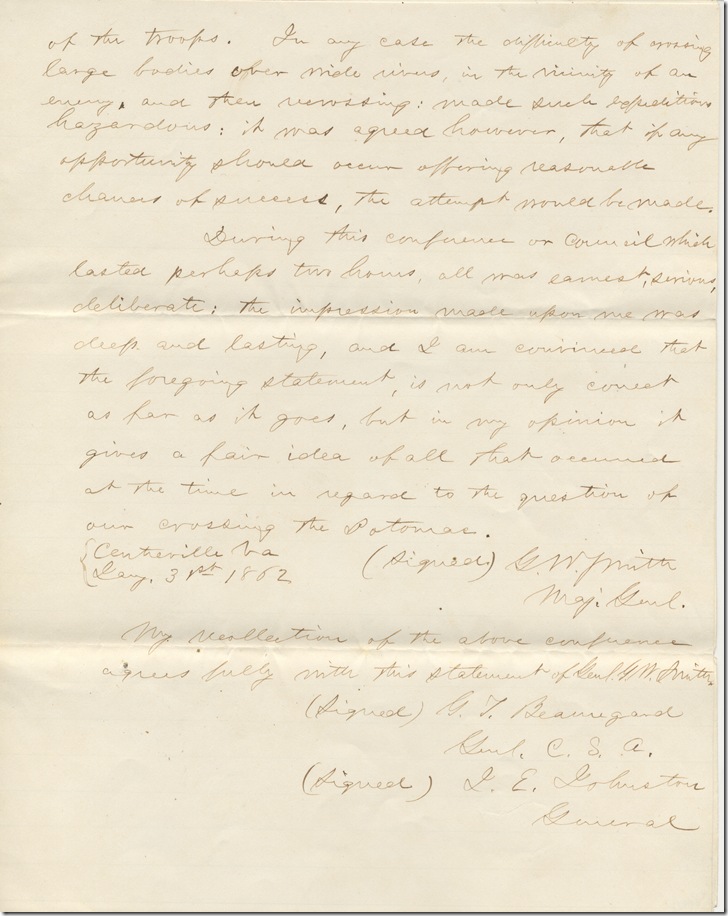

During this conference or council which lasted perhaps two hours, all was earnest, serious, deliberate; the impression made upon me was deep and lasting, and I am convinced that the foregoing statement, is not only correct as far as it goes, but in my opinion it gives a fair idea of all that occurred at the time in regard to the question of our crossing the Potomac.

Centreville Va

May 31st 1862

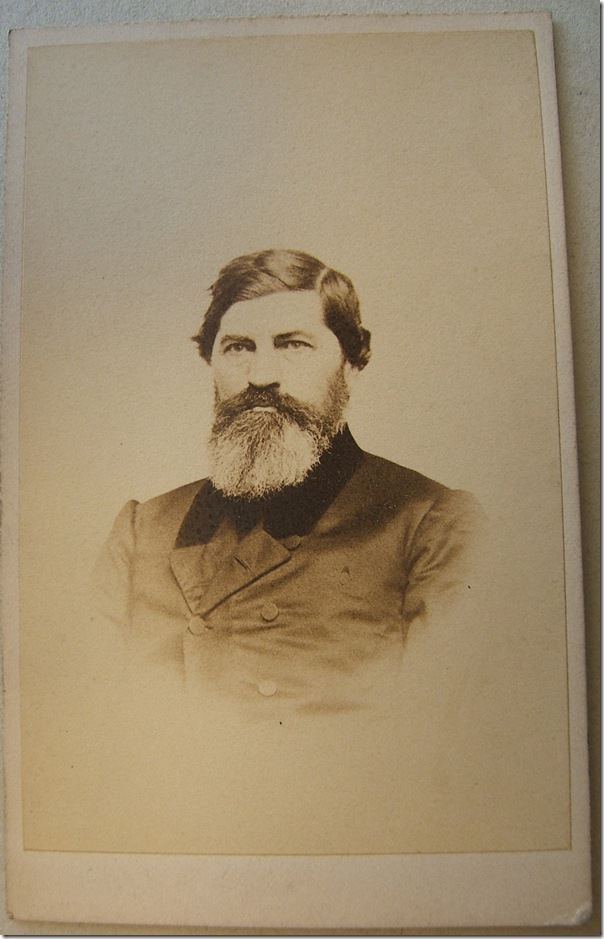

Signed G. W. Smith

Maj. Genl.

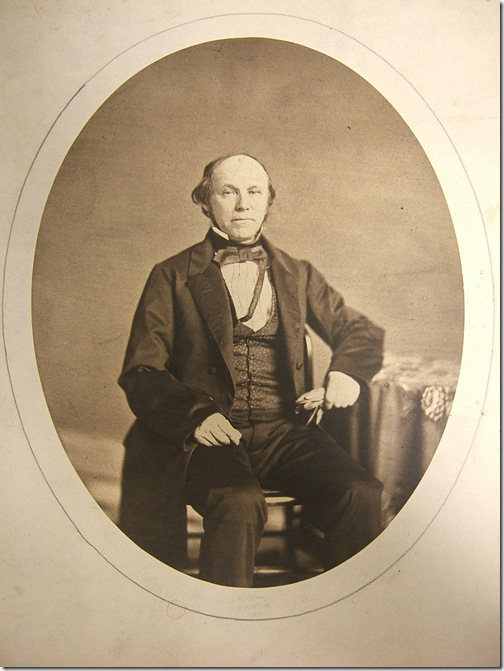

My recollection of the above conference agrees fully with the statement of Genl. G. W. Smith

Signed G. T. Beauregard

Genl. C. S. A.

Signed J. E. Johnston

General

Citation: Gustavus Woodson Smith (1822-1896), Statement of a conference at Fairfax C.H. Sept. 26th 1861. Centreville, Va, 31 May 1862. AMs 356/17